this essay was originally penned in august ‘23.

I recently read an online piece which discussed masculinity and femininity, and it prompted me to reflect on personal musings surrounding formations of the feminine and masculine in the early part of my life.

As a young girl, I hated my hair. After each beauty shop appointment, which was every two weeks, when my mother would pick me up I’d beg her to allow me to cut my hair; she always refused.

To mark my defiance and visibly show contempt after she told me “no,” I would put my hair in a ponytail. My internal hatred for my hair at an early age wasn’t unwarranted. In elementary school, someone stuck gum in my hair on two separate occasions.

Aside from the painstaking process of removing chewing gum from one’s hair, which my mother laboriously toiled using peanut butter, it caused me a lot of attention. Peoples’ initial remarks toward me always included references to my hair, both black and white.

“Your hair [in two black shiny ponytails] doesn’t look like the other girls’. What are you?” I can recall one elementary teacher asking.

Growing up, I never consciously knew hair was a signifier of beauty, nor that it could be perceived as some sort of ideal for people.

In fact, it was not something I thought about at all, much in the same way people of lighter shades do not think about colorism. As a young child then, all I remember is hating the attention and deflecting as a coping mechanism.

Upon reading an honestly gripping memoir [last summer] intimately tied to both beauty and identity, I’ve been thinking about my earliest formations of who or what I aspired to look like.

The tale of my socialization in 2000s youthdom is an entirely separate story, yet I can earnestly say that, before I entered college, I did not have any real self-identification or conceptualization of beauty.

Sure, I indulged in drug store makeup, mostly powders and eyeliner, and occasionally splurged on high-end lip-glosses in high school, but I didn’t necessarily have an ideal feminine form of myself. Ironically, the archetype I sought to emulate, or rather I saw myself in, was a man: it was Tupac.

I remember the first time I shaved my unibrow in the fourth grade — it was a thrill. It was so satisfying to lather the soap and slide the disposable razor neatly and slowly between my eyebrows.

When my mother noticed and asked why I did it, I told her an older boy on the bus made it a point to tell everyone I had a unibrow. She took the razor from me, but, for two years, I would sneak and glide the razor, gently, as to not bring too much attention to my face.

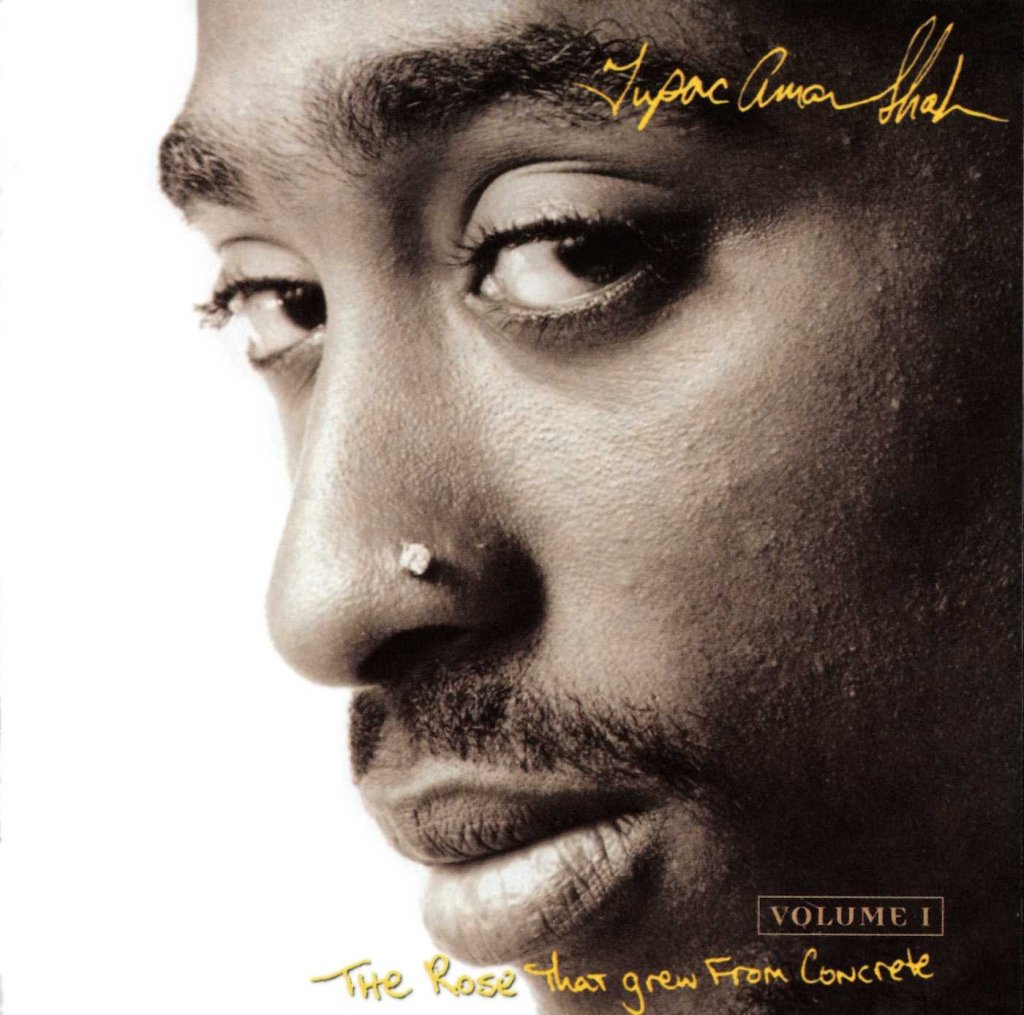

This changed my sixth grade year when I checked out Tupac’s poetry book The Rose that Grew from Concrete from the middle school library. If you’ve ever seen the cover, and if you haven’t you should Google it, his features are splendidly captured in Sepia, a three quarter profile view with his unibrow on full display.

I remember looking at the cover and being mesmerized by his face. I thought he was the most beautiful human being; I grew my unibrow back and became obsessed. Subconsciously, perhaps, I think this shaped the way I saw myself, through him.

Even when I started getting my eyebrows threaded, I would always ask the aesthetician to leave part of the middle and to “never take too much off”.

This Tupac fanaticism was held well throughout my tweens, eventually waning after adolescence, though it prompted me to think, especially after reading said memoir, deeper about how this now-passé ideal could be interpreted in the eyes of others.

As nearly everything is over rationalized nowadays, I am certain there exists numerous explanations, across disciplines, which can attempt to explain what this may indicate. However, I lean into the posture that beauty is immensely difficult for us to talk about because its essence is otherworldly; the essence is the why.

Depending on where you fall on the spectrum of religion and spirituality, you may either accept or reject this claim. Nonetheless, as cliché as it sounds, there is beauty in everything and we cannot always explain it. There is no quantifiable variable or explanation for “why” and, for intelligent beings, that is difficult for us to passively accept, but it just is.

Beauty, like music, is something we experience. When we hear a sound it awakens something in the brain that was once dormant, and we are forever changed; beauty holds a similar bearing. We experience beauty, or what we perceive it as, and are moved, compelled really, to understand its origins and how it came into existence.

However, unlike music beauty is observational; we draw the experience in with the eyes. There is a reason why the beauty industry — haircare, skincare, fragrance and makeup — consistently grosses upwards of $430 billion dollars annually, and I don’t disclose this figure to critique or even influence anyone’s beauty practices.

I simply want to call attention to how seriously we are transformed by our ideas of beauty, much more than we — I do believe — are honestly and ready to admit.

love & madness,

Leave a comment